Background

In 2020, when I was new to programming, I stumbled upon a course on functional programming. The link is no longer available, but I distinctly remember one assignment: implementing a concise JSON parser. Although I used JSON constantly in web development, I had never considered how it was actually built. Realizing its syntax was recursive, I couldn’t immediately wrap my head around it, planting a seed of curiosity that stayed with me.

In 2021, I studied compiler theory and built a compiler for a C-like language. By 2022, I wrote an article introducing algorithms for parsing JSON syntax, accompanied by a rough implementation.

This year, I decided it was time to build a comprehensive JSON library, encompassing serialization, deserialization, and all necessary configuration parameters. I chose Python’s standard json library as my target. After finishing it, I realized the project didn’t actually require complex, abstract compiler knowledge. The real challenges lie in software engineering and the myriad details regarding string encoding.

I hope this article gives interested readers a taste of the fun and difficulties involved in implementing a robust JSON library. You can find the source code here. It will be easier to grasp if you follow along with both the article and the code, though you are certainly welcome to skip the source and try building it yourself.

Python’s json library actually consists of two versions: a pure Python implementation and a C extension. The Python source is located at /Lib/json, while the C extension is at /Modules/_json.c. The author’s goal was to ensure speed while maintaining compatibility with pure Python environments (like PyPy). Since my current work focuses on Python, I implemented the features using only pure Python. When I started, the latest source code on GitHub was for Python 3.15, so I based my work on that version. (This decision, however, caused some obstacles later on—a lesson learned from my first attempt at reproducing an open-source library).

The project took about three weeks, and I passed almost all official test cases. The only exceptions were:

- C-extension specific tests: Since I didn’t use C.

- Command-line tool tests: As mentioned, I used the 3.15 source code (specifically for the tests). However, when I started coding, the latest available interpreter was 3.14. Consequently, some APIs used in the 3.15 tests were missing in my 3.14 interpreter, preventing those tests from running.

Additionally, I did not implement detailed error messaging for JSON parsing. Since this is a helper feature not covered by the official test cases, I skipped it.

The project consists of roughly 700 lines of application code and 800 lines of test code. It is worth noting that the ratio of application code to test code is approximately 1:1.

In fact, it only took me two or three days to implement the basic loads and dumps functionality. However, I ran into difficulties with the configuration parameters later on. The sections involving Unicode and Escape characters were particularly obscure, requiring significant effort and research to understand.

Using AI and Official Source Code

Since my goal was to gain a deep understanding of the JSON library, I didn’t rely on AI to generate the core code for me. I primarily used it to research specific details regarding Unicode and escape characters in JSON. In the past, this would have been akin to “digging through dusty archives”—tedious grunt work that I have zero interest in doing manually.

I also consulted the official source code for some of the nitty-gritty Unicode handling—specifically, how to determine if a raw byte stream is UTF-8, UTF-16, or UTF-32, as well as handling Big Endian vs. Little Endian distinctions. These details are a bit too trivial and specific for me to memorize, as I will likely rarely need them again. However, when building the deserialization feature, I did use AI to generate the regular expressions for the lexer, as I wasn’t very familiar with regex syntax at the time. I later tweaked and refined the generated code myself.

The Story Behind the Author: Bob Ippolito

Whenever I study a piece of software, I’m always most fascinated by the story of the person who built it. The author is Bob Ippolito (known as etrepum on GitHub). He created simplejson as a third-party library, and it was later incorporated into the official Python standard library.

Judging by his blog and repositories, Bob’s interests span Haskell, Python, Web software, Erlang (he authored mochiweb), and JavaScript. He even built a Khan Academy-style website to teach children programming.

Looking at his background, his first internship was in 1997, making him a true veteran of the original dot-com boom. To date, he has worked at over ten companies, moving frequently and often serving as CTO. After his company was acquired in 2012, he spent a brief stint at Facebook. Currently, he is “retired” and volunteers with a California non-profit (Mission Bit), teaching programming to high school students. From small startups and tech giants to successful exits and educational outreach—this is exactly the kind of diverse career path I aspire to!

His technical breadth is incredibly wide, covering web software, games, RFID, iPod software, and even iOS virtualization (running iOS apps in a browser).

All in all, he is the quintessential Hacker: broad interests, deep technical expertise, a pure love for coding, and a passion for teaching others.

Implementation Strategy

Fundamentally, JSON is a subset of the JavaScript language used for describing data structures. Approaching it from this perspective makes it much easier to grasp the big picture.

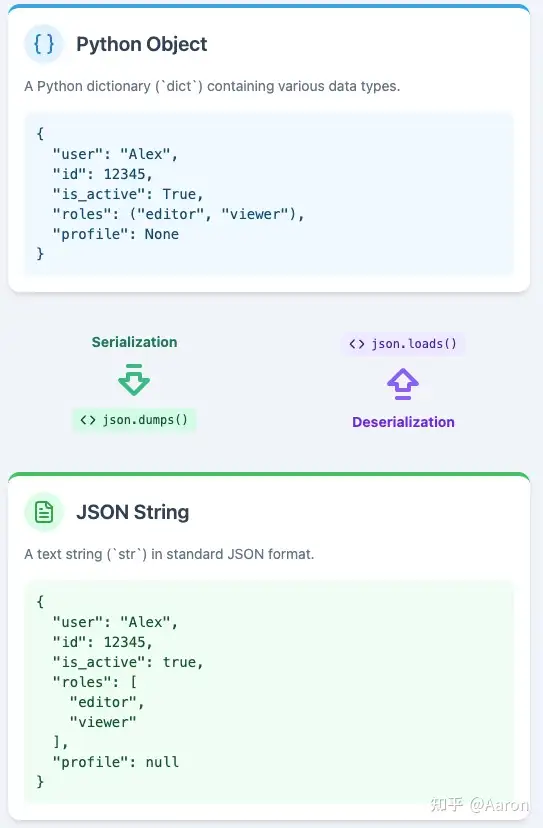

The functionality of the standard library can be categorized in two ways. The first is by operation: serialization (converting Python data structures into JSON text) and deserialization (converting JSON text back into Python structures). The second is by scope: core functionality (the basic conversion logic) versus configuration parameters (options for handling JSON supersets, error tolerance, formatting, etc.).

Below are the function signatures from the standard library. Each parameter controls a specific behavior. For instance, parse_constant allows for a JSON superset (supporting floating-point types beyond the official spec), while check_circular performs cycle detection on data structures to prevent infinite loops.

def loads(s, *, cls=None, object_hook=None, parse_float=None,

parse_int=None, parse_constant=None, object_pairs_hook=None, **kw):

pass

def dumps(obj, *, skipkeys=False, ensure_ascii=True, check_circular=True,

allow_nan=True, cls=None, indent=None, separators=None,

default=None, sort_keys=False, **kw):

pass

In terms of dependencies, serialization and deserialization can be implemented independently, while the configuration parameters rely on the core functionality.

I planned to first read through the JSON RFC and Official Documentation. Then, I would attempt to implement the basic serialization and deserialization logic. During this phase, I wrote my own test cases based on intuition and typical usage patterns.

Let’s focus specifically on the architecture and algorithms behind the deserialization process.

The most critical step is understanding the “grammar” section of the RFC to identify the symbols that constitute JSON. Next is grasping the syntactic structure, which is divided into primitive types and structured types . Since structured types are recursive, the implementation requires significant use of recursive operations.

Once that is understood, the problem can be broken down as follows:

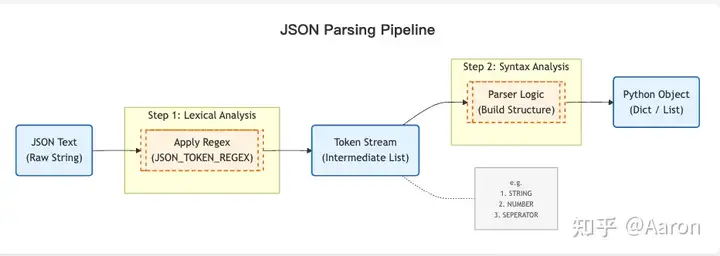

The data flows through three stages: JSON text , tokens (an intermediate stage where the string is broken into meaningful subunits), and finally the Python object . This process consists of two steps: first, Lexical Analysis (converting JSON text to tokens), and second, Syntax Analysis (converting tokens into Python objects).

I adopted a classic compiler architecture here, transforming the data step-by-step into a format closer to the target. While the official library uses a high-performance approach that trades off some readability, my approach is more structured. While simple grammars can be parsed in one go, modern compilers (like those for Go or Python) typically use this two-step parsing method.

Regarding token parsing, let’s skip the heavy compiler theory and approach it with simple intuition. Consider the following string:

“3 5 2 8 6”

Suppose we want to sort the numbers within this string. How would we proceed? Intuitively, we need to convert it into a data structure that supports sorting and comparison. Naturally, we would split it into a list and convert each element into a number, like this:

>>> b = map(lambda x: int(x), "3 5 2 8 6".split())

>>> list(b)

[3, 5, 2, 8, 6]

The logic here is identical. Using regular expressions, we can directly convert the JSON text into individual tokens. Each token is a meaningful unit containing a type and a value. Here is a typical example:

"""

{

"name": "Project Alpha",

"version": 1.2,

"is_active": true,

"metadata": null,

"developers": [

{"id": 101, "role": "lead"},

{"id": 102, "role": "backend"}

],

"description": "A test string with an escaped quote \\" here."

}

"""

[

("SEPERATOR", "{"),

("STRING", '"name"'),

("SEPERATOR", ":"),

("STRING", '"Project Alpha"'),

("SEPERATOR", ","),

("STRING", '"version"'),

("SEPERATOR", ":"),

("NUMBER", "1.2"),

("SEPERATOR", ","),

("STRING", '"is_active"'),

("SEPERATOR", ":"),

("LITERAL", "true"),

("SEPERATOR", ","),

("STRING", '"metadata"'),

("SEPERATOR", ":"),

("LITERAL", "null"),

("SEPERATOR", ","),

("STRING", '"developers"'),

("SEPERATOR", ":"),

("SEPERATOR", "["),

("SEPERATOR", "{"),

("STRING", '"id"'),

("SEPERATOR", ":"),

("NUMBER", "101"),

("SEPERATOR", ","),

("STRING", '"role"'),

("SEPERATOR", ":"),

("STRING", '"lead"'),

("SEPERATOR", "}"),

("SEPERATOR", ","),

("SEPERATOR", "{"),

("STRING", '"id"'),

("SEPERATOR", ":"),

("NUMBER", "102"),

("SEPERATOR", ","),

("STRING", '"role"'),

("SEPERATOR", ":"),

("STRING", '"backend"'),

("SEPERATOR", "}"),

("SEPERATOR", "]"),

("SEPERATOR", ","),

("STRING", '"description"'),

("SEPERATOR", ":"),

("STRING", '"A test string with an escaped quote \\" here."'),

("SEPERATOR", "}"),

]

The underlying regular expression looks like this:

JSON_TOKEN_REGEX = re.compile(

r"""

# 1. 字符串 (最复杂,优先匹配)

(?P<STRING> " (?: \\. | [^"\\] )* " )

# 2. 数字

| (?P<NUMBER> (-? \d+ (?: \. \d+ )? (?: [eE] [+-]? \d+ )? | Infinity | -Infinity | NaN ) )

# 3. 字面量

| (?P<LITERAL> true | false | null )

# 4. 分隔符

| (?P<SEPERATOR> [{}[\],:] )

# 5. 空白 (需要被忽略)

| (?P<WHITESPACE> \s+ )

# 6. 错误/不匹配项 (用于捕获非法字符)

| (?P<MISMATCH> . )

""",

re.VERBOSE,

)

Once I had the tokens, I used a Python deque to store them. Since the process involves frequently popping the first element, and deque is implemented as a linked list, this operation has a time complexity of O(1).

Next, we tackle the primitive types. If the token is null, we return Python’s built-in None. For true and false, we return Python’s True and False. Numbers and strings follow the same logic.

Structured types are slightly more complex, but we simply need to follow the grammar rules. Taking Arrays as an example, the Array tokens will always follow this format:

array = begin-array [ value *( value-separator value ) ] end-array

For example:

[1, 2, 3]

We remove the start symbol, recursively parse the first element, remove the separator, parse the next element, and so on.

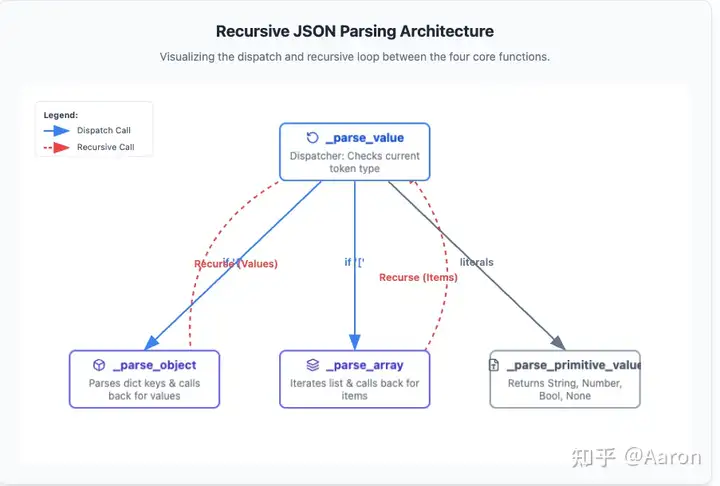

The architecture relies heavily on mutual recursion. An Array might contain another Array, or an Object might contain another Object.

There are four distinct functions: _parse_value (handles any JSON value), _parse_primitive_value (handles primitives like null, strings, etc.), _parse_object, and _parse_array.

This approach stems directly from the JSON grammar itself. By following the grammar, we naturally arrive at this classification and recursive relationship.

Serialization is essentially just string concatenation. We can apply the same logic of handling primitive and structured types to build the output string.

Once implemented, I attempted to pass all the official basic test cases. The workload for the basic serialization and deserialization was surprisingly light—it only took me two or three days. The remaining test cases mostly revolved around configuration parameters, such as default, ensure_ascii, and check_circular.I simply went through the test cases, consulted the relevant documentation, and implemented these features one by one.

Key Challenges

The most difficult aspect of this program is the recursive logic. Since recursive programs are not linear, they are inherently counterintuitive.

However, having written a significant amount of recursive code while learning functional programming, I am quite comfortable with it now. That said, tracing the data flow during debugging remains difficult, and it caused quite a few headaches during subsequent performance testing.

What truly surprised me was the configuration parameters for serialization; this actually accounted for the bulk of the workload. Three features were particularly complex: the circular reference detection algorithm, formatting, and the handling of special characters in strings.

Cycle Detection : In languages like Python and JavaScript, data structures can contain cycles. For example:

a = {"b": None}

b = {"a": a}

a['b'] = b

print(a)

# {'b': {'a': {...}}}

Attempting to serialize such a cyclic data structure directly would cause the program to hang, as serialization requires traversing the entire structure. Therefore, we need some basic graph theory to detect cycles in a directed graph. While “graph theory” sounds abstract, it is quite concrete here. Don’t worry—let’s use a real-world intuition: if you get lost in a forest, what do you do? Naturally, you leave markers—like stacking stones or arranging sticks—in places you have already passed.

Detecting cycles in a graph works the same way. During traversal, if we encounter a node we have already visited, we know there is a cycle and raise an error. Initially, I used a set to store visited nodes, but this failed the official test cases. Upon closer inspection, I discovered another scenario: shared references.

a = True

b = {"b": a}

c = {"c": a}

In this case, there is no cycle, but the brute-force algorithm described above would incorrectly identify one. So, I had to update the algorithm: for compound structures, we record Array and Object nodes, but crucially, we must remove the node from the marker set once we finish traversing it (i.e., when exiting from this node).

Formatting : Formatting seems simple, but there are many edge cases. Ultimately, I borrowed a concept from React: abstracting a state value to represent the indentation level . During recursion, I increment or decrement this state value. Then, during rendering, the indentation is applied based directly on this state. By separating state from rendering, the problem is decomposed into two independent parts, making it much easier to solve.

Just like with JSON parsing, I had to start with the simplest cases and incrementally handle increasingly complex scenarios.

String Handling : This presented two main challenges.

The first was escape characters . I had to carefully study the types of escape characters. Since JSON escape sequences don’t map one-to-one with Python’s, a re-mapping process was necessary. I needed to understand every type and map them meticulously.

This work included:

- Handling quotes

". - Handling backslashes

\caused by escaped quotes. - Handling legacy ASCII control characters like

\n,\t, etc. - Handling Unicode escapes. For example, the Greek letter α becomes

\u03b1, and the emoji 😀 becomes\U0001f600(which eventually converts to the surrogate pair\ud83d\ude00). The hexadecimal number here is the Unicode code point —think of it like an ID card number—which is then converted into the underlying binary byte encoding.- This also involves the concept of the BMP (Basic Multilingual Plane). You can think of the BMP as a set. The original designers didn’t anticipate Unicode covering so many characters, so they limited code points to four hexadecimal digits (within the BMP). As the character set grew beyond the BMP, algorithms were introduced to represent these out-of-range code points using two four-digit hex values (surrogate pairs). The JSON library parser must implement these algorithms. (I admit, reading about this made my head spin—it involves very low-level encoding details).

The second challenge was Unicode encoding . JSON is compatible with UTF-8, UTF-16, and UTF-32, so the parser must determine the encoding format when receiving a byte stream. For this, I chose to refer directly to the official source code because the detection logic is quite tricky.

Additionally, the JSON library has a feature similar to JavaScript “downleveling.” When a new JS version is released but not yet supported by all environments, software often compiles new JS into an older version. For the JSON library, the ensure_ascii feature serves a similar purpose. It converts all Unicode strings into ASCII escape sequences so that environments supporting only ASCII can still parse the data. This required understanding the BMP concept and conversion rules—I’m grateful to AI for saving me a lot of research time here.

One final point is that the features are not entirely orthogonal . For example, the default function interacts with the cycle detection algorithm. I didn’t consider this at all initially and only realized it after hitting the official test cases.

My takeaway is that managing this requires someone intimately familiar with the library. You can’t rashly introduce new features that affect old ones. This goes beyond pure programming; it requires a product manager or project management perspective. If ten features interact with each other, the number of relationships creates a combinatorial explosion. If this isn’t managed well, the maintenance cost of the software will skyrocket.

Source Code Review and Comparison

After passing all the test cases, I naturally moved on to reading the official source code, specifically the pure Python implementation within the standard library.

My first impression was that the code is incredibly seasoned and concise. The serialization logic, in particular, is very clean and structured. It makes extensive use of higher-order functions passed as configuration parameters—such as parse_float and parse_int. Even the parsing of Arrays and Objects relies on these injected functions, creating a very uniform and consistant feel throughout the codebase.

Regarding deserialization, the author uses a single-pass approach: scanning the string and constructing the mapped Python data structures simultaneously as tokens are parsed. This makes the code harder to write and read because two distinct steps are compressed into one, but the benefit is significantly higher performance.

However, there are downsides. The source code implements both a C extension and a pure Python version, wrapped in a thin layer of Python OOP-style APIs. Internally, however, the core logic relies heavily on standalone functions and higher-order functions passed around to simulate OOP. This is a classic C-style approach. As a result, the Python code feels very “C-like,” which makes the logic a bit convoluted to follow.

For example, the author implemented a function called make_scanner. To maintain consistency between the C and Python versions, they used a typical C pattern: passing a context object to transfer class methods and data. In idiomatic Python, make_scanner could simply have been a method of the class itself.

def py_make_scanner(context):

parse_object = context.parse_object

parse_array = context.parse_array

parse_string = context.parse_string

match_number = NUMBER_RE.match

strict = context.strict

parse_float = context.parse_float

parse_int = context.parse_int

parse_constant = context.parse_constant

object_hook = context.object_hook

object_pairs_hook = context.object_pairs_hook

memo = context.memo

Originally, I hadn’t planned to release my own source code. However, I realized that the official library sacrifices readability for the sake of performance and C-extension compatibility. Since my implementation offers better readability while still providing complete functionality, I decided to share it as a reference for readers.

Performance Testing and Analysis

While studying JSON, I stumbled upon a JSON benchmark repository on GitHub. I decided to use its data to benchmark my implementation against the standard library’s Python and C implementations. This was my first real encounter with a CPU-intensive program. Previously, when working on backend web software, almost all performance bottlenecks I encountered were IO-bound. The only exceptions were slow database queries requiring indexes, or scenarios where product logic locked full tables, necessitating a switch to Redis.

The tests revealed that the official Python implementation is roughly three times slower than the C implementation. This was surprising; I expected a magnitude of difference (around 10x) between C and Python, but the gap wasn’t that wide.

As for my implementation, serialization took about 1.2 times as long as the official Python version. This is understandable; the official library has subtle optimizations, whereas I prioritized correctness and readability. However, deserialization was a staggering 50 times slower than the official Python implementation!

| Implementation Version | Serialization (dumps) Relative Time | Deserialization (loads) Relative Time |

|---|---|---|

| Official C Extension | 1x (Baseline) | 1x (Baseline) |

| Official Python Impl | ~2x | ~3x |

| My Implementation | ~2.4x | ~150x |

At first, I thought I was misreading the results. After all, I had considered performance and specifically switched to using a deque for efficient token storage. My immediate reaction was that the two-pass scanning strategy—specifically the regular expressions used in the first pass—might be the culprit. However, profiling showed that the first pass (parsing tokens) only accounted for about 1/15th of the total time.

I ran the code through a profiler, but constructing the data structures involves heavy mutual recursion. Unlike a typical linear program (like a server request calling functions A, B, and then C), where bottlenecks are obvious, JSON parsing involves A, B, and C constantly calling each other. This resulted in every function showing similar execution times, close to the total runtime, providing no insights.

I went to play basketball to clear my head, mulling it over the whole time. The next day, I opened the code and noticed the debug logs. It turned out I was generating nearly 1GB of log data. After disabling logging, my implementation’s runtime dropped to about five times that of the official Python version. Considering I used a two-pass scan and maintained a large deque in memory, this performance is within a reasonable range.

The final efficiency comparison is as follows:

| Implementation Version | Serialization (dumps) Relative Time | Deserialization (loads) Relative Time |

|---|---|---|

| Official C Extension | 1x (Baseline) | 1x (Baseline) |

| Official Python Impl | ~2x | ~3x |

| My Implementation | ~2.4x (vs Official Py) | ~15x(vs Official Py) |

After finishing this post, I shared it with a friend who suggested using an generator to handle the tokens, suggesting it might speed things up. So, I attempted a refactor. Fortunately, I had previously encapsulated the tokens into a class:

class Tokens:

def __init__(self):

self._tokens = deque()

def append(self, element):

self._tokens.append(element)

def peek(self):

return self._tokens[0]

def empty(self) -> bool:

return len(self._tokens) == 0

def next(self):

return self._tokens.popleft()

def to_list(self):

return list(self._tokens)

This demonstrates the power of abstraction and encapsulation in software engineering. Initially, tokens was just a list. As I implemented operations like next and peek throughout the code, I realized these operations were highly correlated, so I aggregated them into a class and swapped the underlying list for a deque. Now, switching from a deque to an generator implementation was equally effortless. Because of this encapsulation, the external API remained almost unchanged; I only needed to modify the internal implementation. Combined with my test suite, the refactor was completed easily:

class Tokens:

def __init__(self):

self._tokens = deque()

def append(self, element):

self._tokens.append(element)

def peek(self):

return self._tokens[0]

def empty(self) -> bool:

return len(self._tokens) == 0

def next(self):

return self._tokens.popleft()

def to_list(self):

return list(self._tokens)

Regrettably, the performance didn’t change significantly after the refactor. This confirms my hypothesis: the gap is indeed caused by the fundamental difference between the one-pass and two-pass scanning strategies. The Lua interpreter, for instance, also utilizes a single-pass technique for acceleration.

What I‘ve Learned

First and foremost, for production-level deserialization, a single-pass scan is the way to go. However, high performance often comes at the cost of readability (like rewriting a Python program in C++). It’s always about finding the right trade-off.

Secondly, the official source code makes extensive use of regular expressions. I used to think of regex as a “dirty trick”—clever but unreadable. However, in certain scenarios involving heavy string parsing, regex can replace a lot of manual logic and is incredibly convenient. For example, parsing numbers in JSON format using only if-else logic would be extremely verbose. Furthermore, Python’s regex engine supports a “verbose” mode that allows for indentation and comments, which drastically improves readability. I plan to study regular expressions systematically in the near future.

Thirdly, don’t put official source code on a pedestal. No software is perfect. Official code often has its own downsides due to various compromises. For instance, because the json library provides both Python and C implementations, the Python code is written in a very C-like style, making it somewhat obscure and difficult to read.

Finally, to be honest about the flaws in my own implementation: my understanding of string encoding details in JSON is still lacking. A lot of my code was written while learning on the fly. Since test cases can only cover a finite number of scenarios, my program isn’t robust enough when handling corner cases in strings. In fact, although I passed almost all the official tests, I still discovered a bug related to escape character handling during performance testing.

As John Carmack said, testing cannot solve design problems. Fundamentally, this reflects a gap in my domain knowledge.